Battling Tough Conditions in New River Gorge National Park

On The Fly Freshwater

Photos by Carol Marsh

New River Gorge National Park is among the East’s most scenic destinations. Spanning 70,000 acres of Appalachian Mountain terrain in West Virginia, the view is mostly uphill, especially from a raft floating on New River, which snakes 53 miles through the park.

Decades ago, I sampled the river’s smallmouth bass fishing, drift fishing with the aid of a guide. I caught dozens of smallmouth on a tube jig cast with spinning tackle. However, it wasn’t June 2022 that I returned. This time, I was determined to catch smallmouth bass with a fly.

I attended the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association’s annual conference at The Resort at Glade Springs. As an ancillary trip, I challenged New River’s smallies again, booking a trip with Adventures On The Gorge – Mountain State Anglers Branch.

Unfortunately, heavy rains swelled the river, rendering most of the park’s waters unfishable. While my wife, Carol, and I drove the park’s scenic routes, visited tourist destinations and hiked bankside trails, we watched the whitewater with disappointment.

The appointed day arrived and were bused to Glade Creek access with several other parties. As the others loaded their spinning gear into inflatables, Scott Wake shook my hand and smiled broadly.

“So, you are my fly fisherman,” he said. “I’m glad. I prefer fly fishing.”

Carol carried a spinning rig. It turned out I was the only angler who dared attempt using the long rod. The river’s flow was 18,000 CFS, a volume so extraordinary that this relatively flat section was the only stretch deemed suitable.

“I prefer drought conditions, with a water temperature of 80 degrees,” Wake said. “At 8,000 CFS you have many more opportunities to cast to exposed rocks that hold bass.”

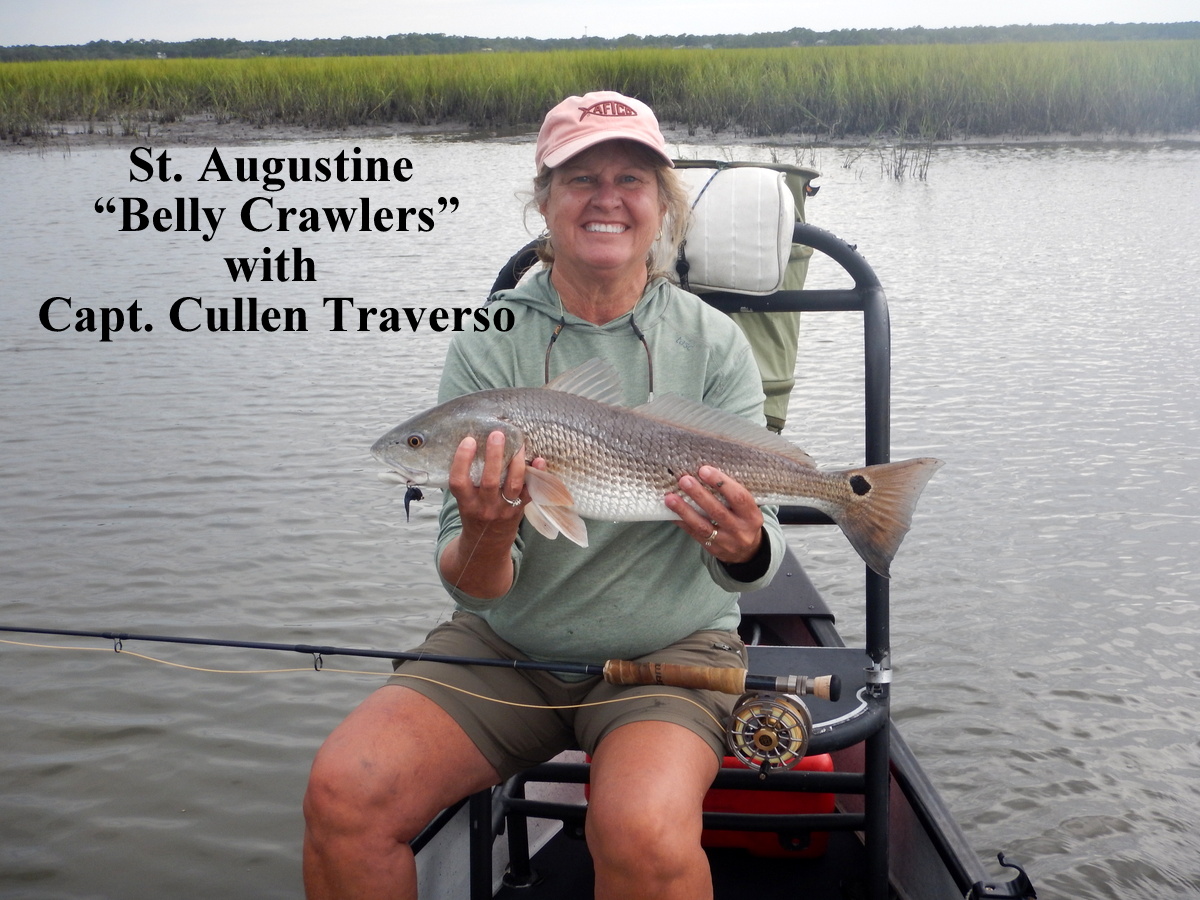

The rainfall caused other detrimental changes in the river, notably dinginess. Scott steadied the boat as Carol seated herself in the stern. Looking at the water, she decided that rather than unfurling a lure from her spinning rod, she would remove the camera from its case. I sat in the bow. Scott was situated in the center, manning the oars. He shoved the boat into the current.

In deference to the difficult task before us, the other guides allowed Scott to be first in line. I fished with a 9-foot, 6-weight Redington Path rod and Redington SVII reel with floating line. The leader was a tapered 13.2-pound test Rio with 10-pound test fluorocarbon tippet. Scott chose a Sneaky Pete popper he had tied.

“I like a 7- or 8-weight rod, but a 6 works,” Scott said. “Cast to cover you see along the bank – downed trees, tree trunks, pockets – especially rocks.”

In drift fishing, the guide essentially steers with oars. The current propels the boat. Extremely fit at age 57, Scott was up to the task. He has guided anglers at New River since 1993 and began as an Oregon whitewater guide in 1984.

At times, a river guide rows the boat across the current, which is no easy feat. We started that way, with Scott rowing to the opposite bank. He oriented the boat parallel to the bank, bow upstream. I stripped line with a couple of false casts and landed the fly near the bank. He used the oars to maintain distances of 30 to 60 feet from the bank throughout the trip. Time after time, I double-hauled line, setting the fly down at the same target or within 3 to 6 feet downstream.

“Perfect,” he said. “I like the way you haul, picking the fly up and setting it down with each cast. Most anglers make false casts, wasting fishing time and missing good spots.”

Alas, making perfect casts is no panacea to fickle fish. I cast to everything visible, tangling the fly in trees a couple of times. Scott stayed vigilant for tree limbs overhanging the river behind, warning me on back casts. He joked every time I snagged a “tree-pounder!”

When the fly snagged, he powered the boat to the tree to free it. When we came to bends with shallow bars, he rowed across the river.

“The one thing you can’t do is dip your oar downstream,” he said. “If it hits the bottom it will snap.”

Midway through the four-hour drift, the boats headed for a bank resting area. Anglers drank, snacked and stretched their legs. I had zero topwater strikes. Other anglers had luck with lures. By the end, one boat boasted a 3-pound smallmouth and a big rainbow trout among 13 landed fish.

Scott discussed changing flies, but we persevered. Reentering the current we fished another half hour before he knotted a Clouser Minnow to the tippet.

The first strike came on the second cast. The fish chased the fly as I hauled it out of the water attempting a hookset.

“That was a nice fish!” Carol said. “Catch it next time so I can get a photo.”

Scott said the trick with a topwater bug was letting it hit the water and not moving it. The fly in the current has all the action it needs to induce strikes. However, with the subsurface fly, everything changed. I saw strikes – line moving, straightening loops, line inching upstream.

“The worst condition for getting strikes is high turbidity,” Scott said. “We are dealing with it the best we can.”

I compensated with fewer casts, stripping fast to remove slack created by diverging currents and whirling eddies. The best odds for tight lines were casts to “pillows,” which is what he called current bulges upstream of rocks.

My last cast hit as we raced toward our takeout point at Grandview Sandbar Access. I was letting the Clouser drift above the shallow bar to remove slack when a bush popped up from beneath the boat, snagging the fly. My only hope was that line would hold, freeing the fly. The leader snapped. “I was going to let you keep that fly,” Scott said. “We lose lots of flies when the flow is this high.”